The Government Accountability Office’s new retirement analysis reviewed nine studies conducted between 2006 and 2015 by a variety of organizations and concluded that generally one-third to two-thirds of workers are at risk of falling short of their retirement savings targets.

However, many of these studies use a “replacement rate” standard: Most commonly, this analysis concludes that you need to replace 70–80 percent of your preretirement income to be assured of a successful retirement. This is a convenient metric to use to convey retirement targets to individuals—and no doubt provides useful information to many workers who are attempting to determine whether they are “on-track” with respect to their retirement savings and/or what their future savings rates should be. However, replacement rates are NOT appropriate in large-scale policy models for determining whether an individual will run short of money in retirement. Why?

Because simply setting a target replacement rate at retirement age and suggesting that anyone above that threshold will have a “successful” retirement completely ignores:

- Longevity risk.

- Post-retirement investment risk.

- Long-term care risk.

In fact, looking at just the first two risks above, if you use a replacement rate threshold based on average longevity and average rate of return, you will, in essence, have a savings target that will prove to be insufficient about 50 percent of the time. Of course, this would not be a problem if retirees annuitized all or a large percentage of their defined contribution and IRA balances at retirement age; but the data suggest that only a small percentage of retirees do this.

In contrast, EBRI has been working for the last 14 years to develop a far more inclusive, sophisticated, realistic—and, yes, complex—model that deals with all these risks. It’s our Retirement Security Projection Model® (RSPM), and produces a Retirement Readiness Rating (basically, the probability that a household will NOT run short of money in retirement).

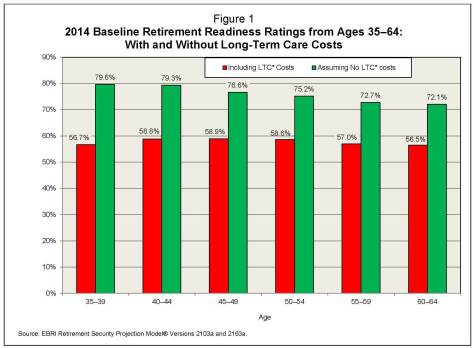

Our

most recent Retirement Readiness Ratings by age are shown in Figure 1

(left). Our baseline results do include long term care costs (the red

bars), but we also run the numbers assuming that these costs are NEVER

paid by the retirees (the green bars). This latter assumption is not

likely to be realistic for many retirees, but we include it to show how

important it is to include these costs (unlike many other models).

Our

most recent Retirement Readiness Ratings by age are shown in Figure 1

(left). Our baseline results do include long term care costs (the red

bars), but we also run the numbers assuming that these costs are NEVER

paid by the retirees (the green bars). This latter assumption is not

likely to be realistic for many retirees, but we include it to show how

important it is to include these costs (unlike many other models).

Even more important is Fig. 2 (right), which shows Retirement Readiness Ratings as a function of preretirement income AND the number of future years of eligibility for a defined contribution plan for Gen Xers.

Even

controlling for the impact of income on the probability of a successful

retirement, the number of future years that a Gen Xer works for an

employer that sponsors a defined contribution plan will make a

tremendous difference in their Retirement Readiness Ratings (even with

long-term care costs included).

Even

controlling for the impact of income on the probability of a successful

retirement, the number of future years that a Gen Xer works for an

employer that sponsors a defined contribution plan will make a

tremendous difference in their Retirement Readiness Ratings (even with

long-term care costs included).

The evidence from EBRI’s simulation modeling certainly agrees with the GAO that a significant percentage of households will likely run short of money in retirement if coverage is not increased. However this is because we model all the major risks in retirement and do not simply assume some ad-hoc replacement rate threshold.

Moreover, using an aggregate number to portray the percentage of workers at risk for inadequate retirement income is really missing the bigger picture. The retirement security landscape for today’s workers can be bifurcated into those fortunate enough to work for employers that sponsor retirement plans for a majority of their careers vs. those who do not. In general, those who have an employer-sponsored retirement plan for most of their working careers appear to be well on their way to a secure retirement.

Perhaps the focus of any retirement security reform going forward needs to be on those who do not work for employers offering retirement plans and those in the lowest-income quartile.

—————————————————————————

Jack VanDerhei is research director at the Employee Benefit Research Institute.